Laughing to Transgress

"A sense of humour is a reflection of a sense of proportion. It occurs when the wiser part of ourselves short-circuits a closed system of thought."

When I was a kid, mocking your international neighbors was the normal thing to do in Europe. More so there were unofficial rivalries, sometimes mutual, sometimes one-way, embodying cultural and historical stereotypes.

The Dutch told jokes like this about us:

A Belgian construction worker is helping out across the border in the Netherlands, and sees a Dutchman pour coffee from his thermos.

"What's that?" he asks.

"It's a thermos! If you put hot things in it, they stay hot. If you put cold things in it, they stay cold."

"That's amazing! How much do you want for it?"

"It's yours for 25 guilders."

"I'll take it!"

The next day he's back in Belgium and proudly shows off his new find during lunch.

"It's a thermos! I got it from the Netherlands! If you put hot things in it, they stay hot. If you put cold things in it, they stay cold."

"Wow, that's amazing! How does it know?"

In turn, we told jokes about them:

A bus with 50 jolly Dutch vacationers is driving down to the Spanish coast, and stops by a gas station in Belgium.

The driver asks the attendant: "Could I get a bucket of water? My engine is having some trouble with this blistering heat!"

"No problem at all!" He goes out back and returns with a big sloshing bucket.

"Also... do you happen to have 51 straws?"

It's not very complicated. Belgians were dumb, and the Dutch were stingy. These are actually much cleaner jokes than the ones we told, because that included:

"How many times does a Dutchman use a condom?"

"Three times. Once the normal way, once inside out, and the third time as chewing gum."

(This was still in primary school, by the way.)

But this joke has a karmic reverse:

"How many times does a Belgian laugh at a joke?"

"Three times. Once when you tell it, once when you explain it, and the third time when he gets it."

Europa Universalis

A casual search will show that the basic jokes about nationality are so scripted, that you can pretty much substitute any country for any other, and arrive at a joke that has been told some place some time. Like this classic train tunnel joke:

A nun, an attractive blonde, a German and a Dutchman are sitting in a train compartment. The train enters a tunnel, it's completely dark, and suddenly there's a slap. When the train comes out of the tunnel, the German is rubbing his face in pain.

The nun's thinking: "The German man probably touched the blonde woman and she slapped him, and rightfully so."

The blonde's thinking: "That German pervert probably tried to grope me, but got the nun instead, and she slapped him. Good."

The German thinks: "The Dutchman obviously copped a feel on that blonde woman, and she hit me instead of him. That bastard!"

The Dutchman thinks: "Next tunnel, I'm gonna slap that German fucker again!"

The nationalities are close neighbors, and that means there's some sort of stereotypical, historical beef. When you change the countries, the joke's meaning can flip, depending on what your preconceptions are.

For example, when the Dutchman is the aggressor, it could be assumed he is seeking some kind of payback for Germany's aggression against the Netherlands. If you tell the version where a German slaps a Dutchman, he might personify unprovoked German aggression. The main reason the joke gets told with nationalities is the same reason it's a nun and an attractive blonde: it adds necessary color to the situation, so the characters (and the audience) can draw all sorts of wrong conclusions instantly.

It is implied that the nationalities are relevant, but never actually stated. It's misdirection to draw you in. The real punchline is that complicated explanations for simple acts of violence are not necessary. A joke about nationalist aggression can instead let you recognize universal themes, through its 4 contradictory perspectives, which bleed into a host of other sensitive topics.

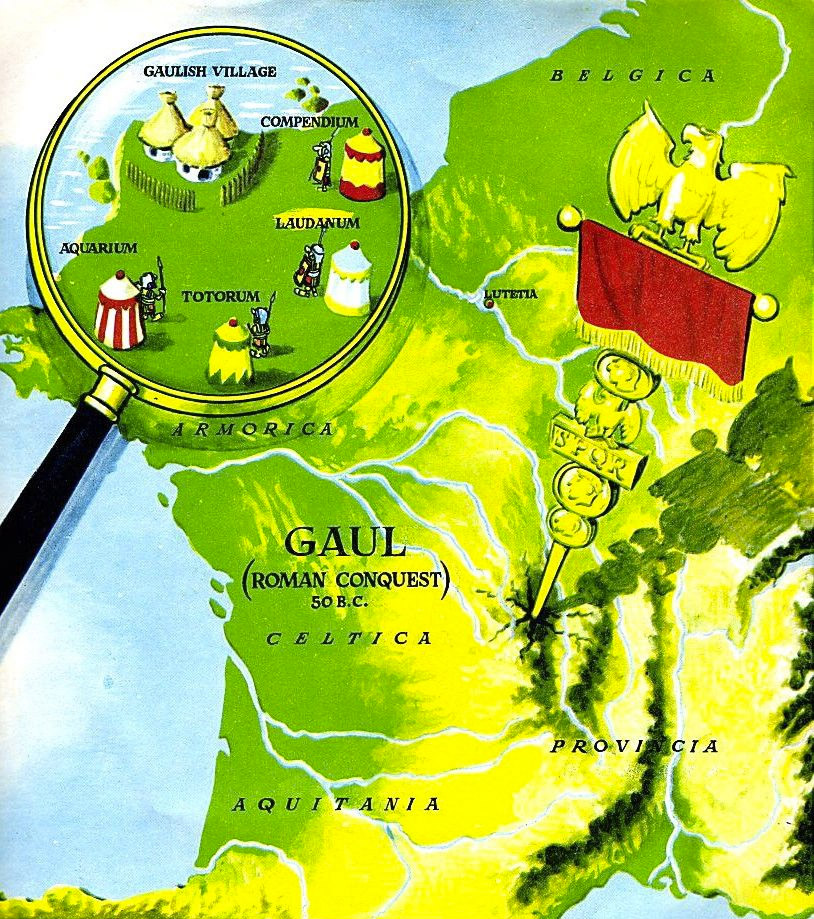

It's important to know the Europe in which such jokes were routinely told was a very different place. The hint is in the "25 guilders" at the start. We didn't always have the Euro, a Customs Union, Schengen-zone visas, and fancy electric trains that connect it all. You only needed to drive a few hours in any direction to arrive at a place where you needed permission to get in, probably didn't speak the language, couldn't tell how much things cost, didn't know the local laws, and couldn't interact with the authorities. Also, these were the same people whose ancestors murdered your ancestors for the last few centuries, but they seemed okay now?

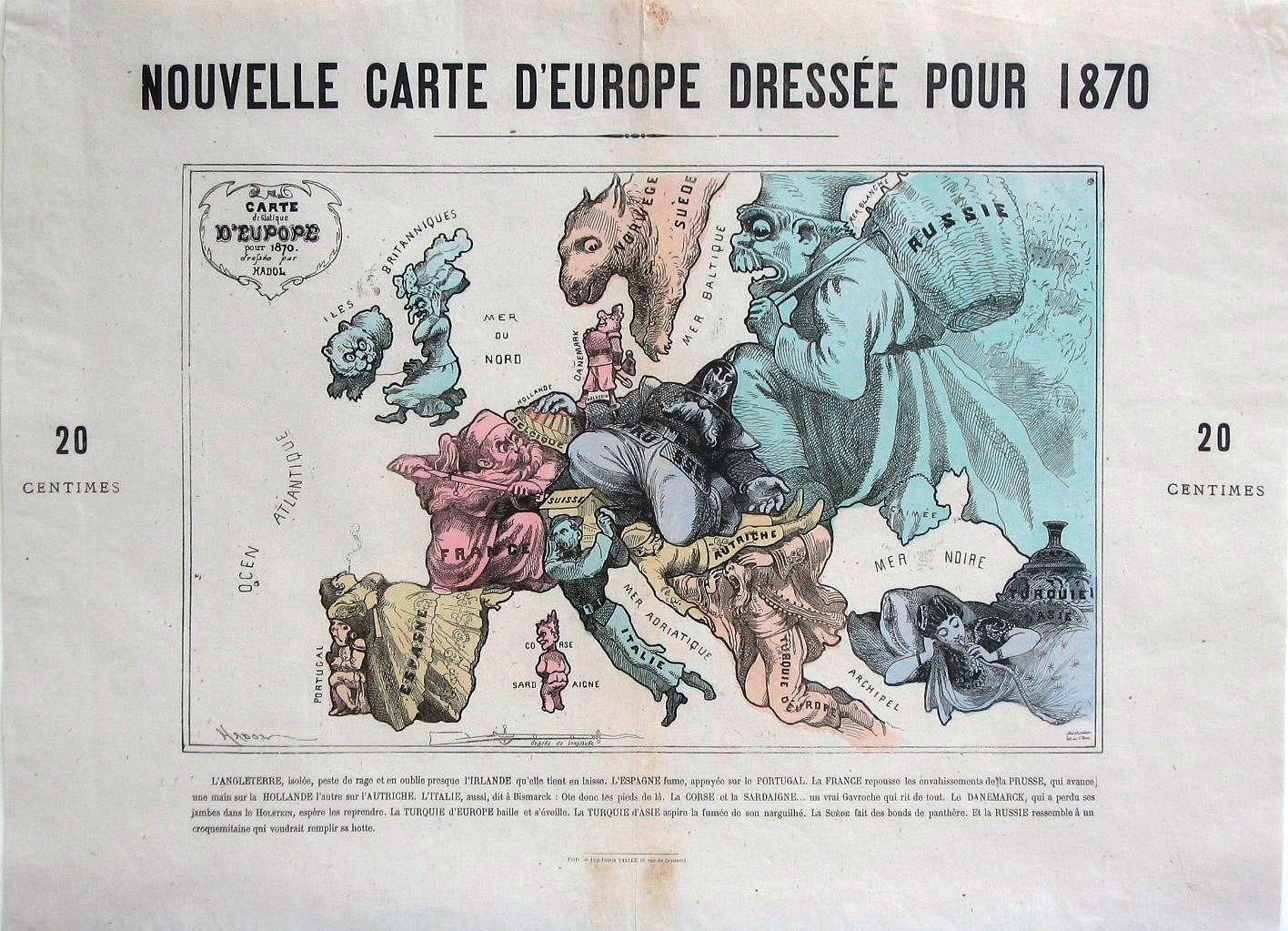

A natural response to having this right on your doorstep was to trivialize and make fun of it. And pretend it was all far away. As if to say: we're all going to be characters in a drama none of us really had any say in, so we may as well have fun with it. Some of these jokes do capture an immense amount of historical and cultural context, for example:

Heaven is where the police are British, the cooks are French, the mechanics German, the lovers Italian and it's all organized by the Swiss.

Hell is where the chefs are British, the mechanics French, the lovers Swiss, the police German and it's all organized by the Italians.

That's a condensed roast of about 150 million people covering at least a century, give or take. Those who crack such jokes don't do so in malice. When the odd Mysterious Stranger actually walked into our town, most of us would be pretty curious and friendly to them. You also wouldn't tell such a joke in front of them, unless you were on good terms (or really bad terms), and had already dropped much of the pretense. The main audience for this was our own tribe, and the goal was to relieve our collective anxiety and fear of the unknown. Letting people in on your jokes about them meant letting them hear something intimate.

In the case of the Belgians and the Dutch, it's right there in the punchlines. Our worry was e.g. that they'd outcompete us with their business acumen. Their worry was e.g. that they'd fail to win against people they considered backwards.

These are universal themes.

Speak Easy

Getting to hear people speak in an unfiltered manner, humorously or not, is an incredibly valuable thing. And I mean for reasons other than quote mining what they said and making them look bad.

One time, I was over at a house of recent friends who didn't yet know I was gay. They were cracking jokes about their gay housemate. The guy apparently used an enormous amount of toilet paper on the regular, which they were attempting to explain by pointing to his assumed sexual activities through the back door. I didn't say anything, certainly didn't want to "come out" then and there. I just laughed along and the moment passed.

There's a certain perspective today that says this was unambiguously homophobic. That such humor is bigoted and degrading to the dignity of the target demographic. That we need to stamp such material with appropriate content warnings, and that those who say it freely should apologize and do penance. That it is not only appropriate but a moral duty to intervene (and conveniently make it all about me in the process).

I for one knew these guys were cracking jokes exactly because they didn't dare bring it up with the person in question. Asking about someone else's toilet issues is not exactly casual small talk. Once you connect humor with taboos, it's really no coincidence that potty humor is a thing.

I also think that if they had known I was gay, they wouldn't have joked around, or been embarrassed after, and then it would have been a Big Thing. The way it went, a concern about a person they shared a house with could be brought up and made legible. I joined the "one of the guys" dynamic, by understanding its rules, context and intent. I can get the same effect now just by saying something funny and insensitive about gay people behind closed doors, to show that it's not a personal landmine at all.

It's also entirely in line with existing LGBT culture. Drag queens in particular have used sass and mockery as a shield, but no mockery is complete without self-mockery. The Adventures of Priscilla: Queen of the Desert (1994) showed everyone how it's done:

The John Cleese quote about a wiser part short circuiting a closed system of thought sounds dead-on to me.

It also reinforces that humor is entirely contextual, because its goal is to dance on the edge of what is actually permissible to say and think. Whatever the current taboos are, whatever's currently the most closed-minded, that's what comedy is most attracted to.

For a great illustration of this, consider two scenes, two years apart. First, the opening to 1999's American Pie:

The lead character is caught jerking off to illegal TV porn by his conservative parents, and the scene is played mostly straight. Situated in its own time as a mainstream American movie, this was pretty raunchy, and reflected common Christian taboos around teenage sex. Particularly when you factor in the titular American Pie which also ends up losing its virginity. A moment so memorable, NYT dedicated a piece to it 20 years later. If anyone was offended by this at the time, it was people who resembled the parents and found it difficult to think or talk about sex without blushing.

These days though, the people who consider this movie offensive would come from the politically opposite side of the spectrum. Reasons cited include the sexism, the gay jokes, and so on. If you believe the press there's loads of detractors now, but really I think they just wanted an excuse to post a video of a young man pretending to fuck apple pie for the clicks.

What's more interesting is how this scene was itself parodied in 2001's Not Another Teen Movie. There's a lot to say about that film, because it's a meticulous fusion of 1980s and 1990s teenage movie tropes. It takes itself not seriously by taking the source material very seriously, with stellar performances. The opening is a direct homage to American Pie, which turns everything about that scene to 11, and exaggerates beyond proportion:

It makes perfect sense when you consider what the common objection was at the time: on-screen teenage sexuality and an acknowledgement of taboo hormonal urges. Instead of a shy nerdy guy with a sock, we have a fearless girl with a comically large pink vibrator. Everyone walks in on it, even grandma and the local pastor. It ends with a whipped cream bukkake, cue the opening titles. The rest of the movie continues this line of subverting source material while throwing in a heavy dose of potty, sex and other gags. It only misses the mark a few times, really, like when it tries to stretch a Token Black Character joke for the entire movie.

If you thought the butt of this was women, or LGBTs, or black people, you'd be missing the point entirely. It was a middle finger aimed at puritan scolds who also spent their time chastizing alien sideboob in video games they had never even played.

Most importantly, audiences thought it was genuinely hilarious.

The Humorton Window

I've mostly stuck to examples that feel dated now, and in the first case, downright provincial.

Jokes about national rivalry have diminished, for the simple reason that the unknown has diminished. After opening European borders, and harmonizing the economic and legal systems, we have a legible continent where countries can easily and freely compare notes. We don't need to joke about who would run things best anymore, we can just go look at the COVID numbers.

When you still encounter this sort of national humor, it's more in the context of April Fools or "shitposting", like the pair of dueling memes:

G E K O L O N I Z E E R D (Colonized)

G E F E D E R A L I Z E E R D (Federalized)

Usually posted by respectively a Dutchman or a Belgian, referring to Dutch imperialism and Belgian bureaucracy respectively, to signify that one demographic seems particularly dominant in a thread or space. It is only properly used when ironic, otherwise it is simply tiresome.jpg.

Sexual humor has also reduced in relevance, because the internet offers unlimited access to both pornography and genuine sex-ed, removing all the basic taboos around it. Rather than a bunch of confused college dudes wondering exactly how gay sex works, you now have guys who tried watching some of it, didn't get aroused by it, and simply moved on.

There are shifting windows of what it is a) acceptable and b) popular to laugh at. There's also a saying, "To learn who rules over you, simply find out who you are not allowed to criticize." This counts doubly so for "or joke about."

This is commonly and falsely attributed to Voltaire but oddly enough appears to originate from a 1993 essay by an actual, genuine, bona fide white nationalist. TIL.

The question of who said it is of course irrelevant, the question is whether it is true or not. A common refutation is that it is disallowed to mock e.g. the mentally disabled, who clearly do not rule over others. But that's a cop out, because doing so lures out those who do have power to punish people for it, namely all sorts of organizations that ostensibly advance the rights of particular groups.

The problem with this system is that it is driven by attention, not by effectiveness. This is described perfectly in the essay The Toxoplasma of Rage, written by recently unmasked blogger Scott Alexander Ocasio-Cortez. When the actions that are rewarded are those that get the most attention, this tends to amplify rather than reduce tensions between different interest groups, by breeding more resentment.

It also tends to confuse the people who already have means and access with those with need of it. As an example of this dynamic, there was a story here a few years ago: an elderly Jewish woman in distress had called a stand-by nurse (iirc). Upon learning that she was Jewish, the nurse scolded her for the collective sins of Israel against Palestine and was rude and unhelpful. I know about this because the next day it was in every major newspaper, after being highlighted by a Jewish interest organization.

The outcome would be very different if e.g. someone was mistreated because they were homeless or a drug addict. It would be pretty much impossible for someone like that to get any serious restitution or acknowledgement here. Whether you call that being in charge or not, it represents two vastly different tiers of access and service, differentiated purely by whom you are not allowed to generalize against.

Another common refutation of not-Voltaire is the success of comedians like Dave Chappelle or Bill Burr, who both brought new material highly critical of cancel culture and organized "alphabet people" (LGBTQIAA2+). They invited prophesied professional and personal doom, but came out more popular than ever. Ricky Gervais' semi-annual Golden Globes speeches are in a similar vein, with the recurring gag that he'll never be invited again, as he roasts some of the wealthiest people to their faces:

Many correctly point out that none of the comedians' careers or lifestyles are in danger. They are multi-millionaires with successful projects under their belts. That is of course why they get to do it. When people who don't have "fuck you money" or big brass balls crack jokes like that, they make themselves a target, and those with means and motive go in for the kill. The saying is of course "find out who rules over you," not over them.

I find this fascinating because it reveals humor as a sort of "Romulan Neutral Zone" on the edge of the usual political Overton Window. This larger zone covers not just what is acceptable, but also what is currently contested. The jokes are the ammo, but the armor is self-confidence derived from skill and success. Comedians play this game on Nightmare difficulty every show night.

This zone consists of ideas which humor is effective at working its magic on. It alters or refutes our worldview with condensed bursts of hidden wisdom or absurdity. But they must be within our grasp to untangle. Humor's range is subject to its own constraints, such as "Too Soon", "That's NOT Funny", "I'm Going To Hell For Laughing" and "I Don't Get It". These are completely subjective limits, which are negotiated and renegotiated between the joke tellers and their audience. If you don't believe me, take the joke about the 51 straws, and replace "Dutch" with "Jewish".

But if you think that means the Jews rule over you, you're refusing to see how these things actually work. What actually rules over you is people's chronic and miscalibrated fear that you might not be kidding, which occurs in highly variable degrees. This might also be a good explanation for the common saying that if you want to tell people something they don't want to hear, you need to make them laugh, or they'll kill you for saying it. Good humor is a successful mental defense against thinking that is too rigid and dogmatic.

The case of Mark Meechan is highly illustrative. This is the Scot who was convicted of "grossly offensive behavior" for teaching his pug-dog to do a Nazi salute, upon hearing "Gas the Jews". He has always claimed he did it purely to annoy his girlfriend. "Justice" in this case includes a court ruling that "context and intent" are officially irrelevant to the matter, an absolute bombshell in legal precedent. But that's not the most absurd part. It's the BBC documentary on the issue afterwards, in which one of the detractors jokingly asks his own cat if it too wants to "Gas the Jews," before concluding no. By the logic of a British court, he is guilty of the same kind of punishable offense, and the video is the only proof necessary.

They looked at a person whose only crime was to make jokes they found offensive, and they thought this made him a credible threat to their entire way of life. In their panicked response, they actually started destroying one of the fundamental foundations of that way of life. They haven't stopped yet.

It's a joke, but the penny has yet to drop.

* * *

Humor seems to be far from just a random evolutionary quirk, or a meaningless pass-time. It is a fundamental mechanism that we individually and collectively use to sanity check ourselves. Humor highlights the boundaries of where we might be wrong, and it helps us cut through hangups and taboo.

It seems to happen when a joke activates surprising and contradictory signals, all at the same time. If we can successfully resolve them using our larger understanding of the world, we can acknowledge something new and true. This also implies that when humor-police shows up, they are a symptom of a collective lack of understanding and of unacknowledged taboos.

When we ban fun and mockery, we ban challenging insights, and we do so at our own peril.